History of Photography

It Takes More Than Skill

My last few articles have been about equipment and scientific photography, and I’ve been feeling the urge to talk about what I love (and hate), taking pictures. So bear with me, I’m going to have to do one of those psuedophilosophical articles again. It started when someone asked me if I considered myself good enough to be a full-time professional photographer. That was easy: NO! My reasoning was that while I consider myself a pretty good out-of-studio photographer (I’m too lighting challenged to be good in the studio), I can’t depend on myself to always get the shot. There are days I produce some excellent work. Other days I shoot from dawn until dusk and after 12 hours in front of the computer, there’s nothing, I mean nothing, to show for it.

I’ll give you an example. A few years ago I went on my dream photo vacation through Scotland and Ireland. I was going to shoot in Rosslyn Chapel (the Davinci Code one), go shooting in the Scottish Highlands and Loch Nes with a local pro, do street photography in Dublin and get to take pictures at a place I’d always wanted to see, the Giant’s Causeway. Oh, and there was a wasted day at Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands. Nothing to photograph there.

You’ve probably figured out the rest of the story, you’ve had it happen too. Of course, all of my best shots were from the ‘wasted’ day in Kirkwall and I got nothing better than snapshots from the Giant’s Causeway. There were some nice shots taken at the Giant’s Causeway that day, all by my fiance who got bored watching me carefully compose and meter my shots and wandered about with my spare camera and lens on full autopilot while she chatted with the other tourists. I’m over it now, truly. The years have passed by. The fact that my 300 Giant’s Causeway images, so carefully composed and metered, are now stored in the darkest corners of my oldest hard drive while two of her full-auto jpgs are beautifully framed and matted in my office room doesn’t bother me anymore. Very much. Except when I’m in my office.

When I’m working through 400 shots trying to find a dozen worthwhile photographs, its easy to assume that other photographers have a better ‘keeper rate’ than I do. And that full-time pros always get the shot and don’t have off days. Someone said something I liked the other day: “When your standing in front of the kitchen sink piled with dirty dishes and look out the window at the neighbor’s pristine front yard, its easy to feel inadequate”. When I’m looking through my piles of not-good-enough images I forget I’ve got some beautiful prints in there, too. The truth is even photographers with 10 times the skill I have miss exposures, don’t see the interesting point of view, or even have an off day. And I have to remind myself sometimes, when looking through a gallery of someone’s superb images that they probably have a hard drive or 3 full of shots they don’t particularly want anyone to see, just like me.

So today I’m going to talk about a few absolutely great, monumental, famous photographs shot by renowned photographers. I’m also going to show some of the other photographs that are closely related, but didn’t make the grade. We’ll walk past their pretty front yard and see if maybe they don’t have a few dirty dishes in the sink, too. All of these are from the days of film, back when the photographer shot the roll and wasn’t quite sure what he or she had until the negatives came out of the developer. Unlike hitting the ‘erase’ button on today’s cameras, those other negatives often got filed away somewhere and resurfaced later.

Raising the Flag

On February 23rd, 1945 the U. S. assault on Iwo Jima was well underway. A 40 man combat patrol, accompanied by a photographer, made its way up Mount Suribachi and at 10:20 a.m. raised an American flag on a section of cast off pipe they found at the top of the mountain, which you can see below:

Not the picture you were expecting? Probably not. This photo, of the first flag raised on Suribachi, was taken by Sgt. Lou Lowery of Leatherneck Magazine. There was a skirmish soon after this and Lowery’s camera was damaged (1 ) Later that day Colonel Chandler Johnson (for a variety of reasons that are somewhat disputed) ordered a larger flag carried up the mountain to replace the first flag (which was rather small). Three photographers, Joe Rosenthal, Bob Campbelll and Bill Genaust, accompanied the second platoon that reached the summit. The newer flag, which was much larger, required a heavier flag pole. A larger piece of pipe was chosen, one that required several men to lift it up.

Rosenthal was shooting with his Speed Graphic camera. Genaust, standing right next to Rosenthal was shooting motion picture film during the flag raising. Rosenthal worked for AP and his film was airlifted out, developed and circulated worldwide within a day of its being taken. Genhaust had movies of the exact same shot as Rosenthal, but that took more time to develop and couldn’t be printed on the front page of the papers a day later. Bob Campbell thought the best shot would be taken from the right of the other two, so he could see both the first flag and second flags simultaneously. Rosenthal’s Pulitzer winning photograph, generally considered the most reproduced photograph in history is below left. Campbell’s shot is below and to the right.

Four great photographers took three photographs and a movie clip of the same event, but only one got the shot and won the Pulitzer Prize. The other shots are simply historical anecdotes.

Migrant Mother

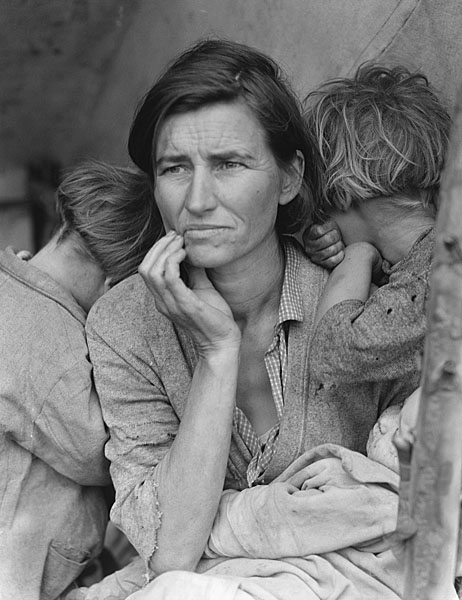

Dorothea Lange was a successful portrait photographer in San Francisco in the 1920s. After the onset of the Great Depression she went on the road as a traveling photographer for the Farm Security Administration and the Resettlement Administration, documenting the plight of displaced and migrant workers from 1935 to 1939. In 1936 she visited a pea-picker’s camp in California where she came upon the makeshift ‘home’ of Florence Thompson and took what became an iconic photograph of the Great Depression, Migrant Mother (below).

The photograph was published the next day in The San Francisco News and created such an outcry that the government sent 20,000 pounds of food to the workers at the camp. By the time the food arrived, though, Florence Thompson and her family had moved down the road to another camp. Ms. Thompson’s identity was revealed 40 years later when a reporter found her living in Modesto, CA. She died in 1983 and her tombstone reads “Florence Thompson — Migrant Mother”. Interestingly, Lange never made any royalties from the photograph (which eventually became a U. S. postal stamp) because she was working for the government when she took the shot (2 ). An unretouched original print of the photograph, though, was sold by her estate for $296,000 in 2005.

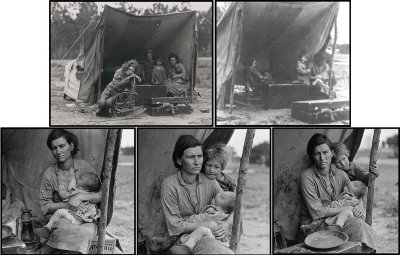

It is a marvelous photograph, but my main interest lies in the other five shots Lange took leading up to Migrant Mother, which was the 6th image. The other five, reproduced below, show the photographer’s progression as she works to get the shot.

The first shot shows the squalor of the living conditions better than any of the others, but its just not powerful, the people look posed and its more about the way they live than showing how their life has affected them. The second is poorly focused and exposed, the third poorly framed; but you can tell Lange is refining her image. The fourth and fifth images are getting closer to what she wanted (in fact the fifth image, not Migrant Mother , is what ran in the San Francisco papers the next day). And then she has it – the last image on her roll, shot even closer, close enough to show the holes worn in the child’s clothes and the worry in the mother’s face. I can’t help thinking if Lange had been shooting digital, she would have been chimping the LCD after each shot, just like I do, checking to see if ‘this one got it’.

The High Wire Act

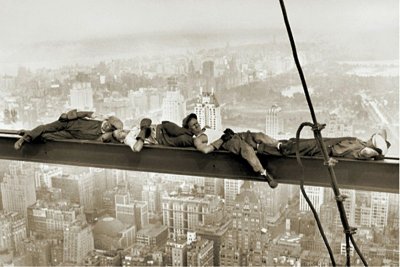

I have long been fascinated by Charles C. Ebbets photographs “Lunch atop a Skyscraper” and “Resting on a Girder”, both taken in 1932 during construction of the GE Building in Rockefeller Center. For anyone with a fear of heights, like me, just looking at these shots is gut wrenching.

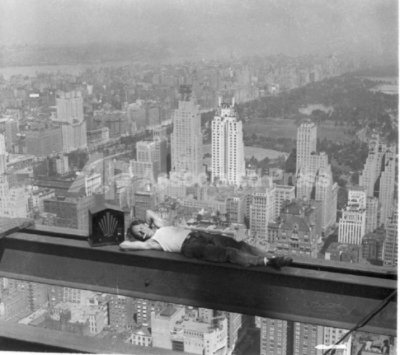

Ebbets wasn’t even credited as the photographer for decades. These photographs, along with many similar images, were owned by the Beckman Archives and the photographer listed as “unkown”. Recently, another image similar image from the Associated Press Archives has been attributed to Ebbets and apparently represents an earlier attempt at these kind of images.

This photograph, while very similar, it is much less impressive. Notice how the photographer’s perspective is looking down on the worker, not nearly parallel like the first two shots. This perspective shows the iron beam to be much wider than it appears in the other photographs, taking some of the drama away. The radio looks contrived (yeah, how are you going to plug it in?). The planking on the upper left shows safe footing is only a short crawl away. Not nearly as terrifying as the other two images. At any rate, I’d have hated to have climbed up that building, gotten home that day with this shot, and hear my editor say “You’ll just have to shoot it again!”

Tank Men

I ended up including this one for two reasons. First, because I’ve always thought the Tank Man of Tiananmen Square was one of the most dramatic images I’ve seen. Second, because this goes to show that not only photographs can miss the rewards because they’re a bit later than the first one published, essays can to. Just before I wrote this blurb, Patrick Witty of the New York Times wrote an extensive and excellent essay Behind the Scenes: Tank Man of Tiananmen which gives much more detail about these photographs than I found. So he beat me to it (and did a more thorough job, to boot 🙂

I’ve long known there were several photographs taken of the Tank Man. Unlike the flag at Iwo Jima, every photographer present ‘got a keeper’ and 4 photographer’s images have been well published. There is a 5th image that neither Patrick Witty nor anyone else knew about until after he wrote his article — the photographer who took the image, Terril Jones, contacted Witty and shared the image after reading Behind the Scenes. Jones’ photograph had never published until now, 20 years after the event, and it shows an entirely different aspect.

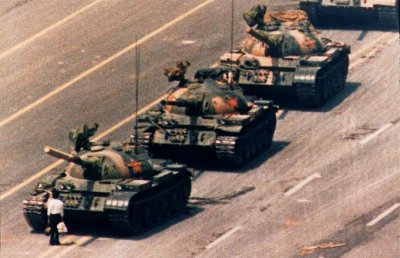

Everyone knows the story of Tiananmen Square and has seen a picture of the ‘Tank Man’. The photographers who took the photos were largely confined to their rooms at the Beijing Hotel and could only shoot from the balconies as they watched the drama unfold. Here are the 4 classic images of Tank Man. You’ve certainly seen some, or perhaps all of them before. Below are the two most widely viewed images, which also happen to be the two most tightly framed. On the left is that shot by Charlie Cole for Newsweek, who probably had the best vantage point. On the right is the image shot by Jeff Widener for AP. Widener’s image is actually quite remarkable: being further from the event he was shooting a 400 f/5.6 lens with a 2x teleconverter (effectively f/11) and because he had run out of is usual ISO 800 film was shooting a roll of ISO 100. The shot on the right was shot at 800mm with an exposure time of 1/30 second!!! That’s some steady hands!

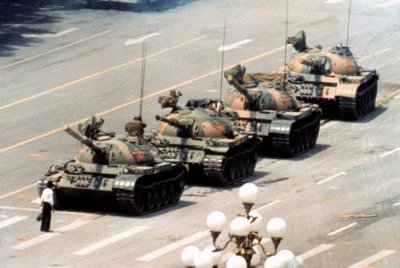

The next two images are taken at a wider angle which shows the width of the street and a burned out bus at the top left. On the left, is the image taken by Arthur Tsang of Reuters, whose vantage point was slightly obstructed, and on the right that of Stuart Franklin for Time Magazine. I love the sequence of the two shots, showing the following tanks coming to rest behind the first.

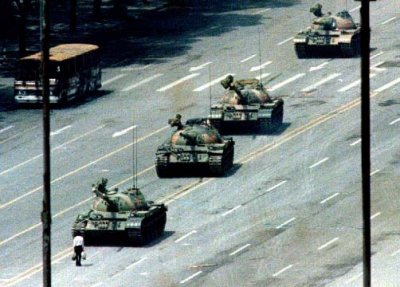

Terril Jones was also working for AP and actually was out of the hotel and down on the street. He heard the tanks coming, heard gunfire and took several quick photographs of people running away from the square before getting to safety himself. It was only a few months later, when looking through his negatives, that he realized he too had photographed the Tank Man, even earlier in the sequence of events than the other photographers. Look to the left between the two tree trunks and at the tanks approaching from the right. The calm of Tank Man now becomes more apparent – in the other images I realized, of course, he could be run over by the tank. I didn’t realize bullets were flying and the street was so empty because everyone but him had run away.

Twenty years after the event, Terril’s shot, which seemed unimportant at the time, is now published because it expounds on the 4 primary photographs. So maybe all those images on my hard drives should stay there, just in case. You never know.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

More Lensrentals Articles

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Devil’s Advocate

-

Photon Jess

-

simon

-

Danny W

-

RioRico

-

RioRico

-

Brian