History of Photography

The Heights and Depths of Nadar: TL;DR Version

- Nadar Rotating Portrait. Circa 1865, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

“He is a man of wit without a shadow of rationality . . . His life has been, still is, and always will be incoherent.” Charles Philipon, describing Felix Tournachon.

Photographers are the most fascinating people. I’m sure there are some that simply spent their life just taking great photographs, but I tend not to notice those. There are too many more who were great photographers and a whole lot more. I write about the ‘whole lot more’ photographers. It can be the photographer who invented strobes and took pictures of atom bombs. Or the photographers that made the fastest automobile of their day. Or the photographer who invented the telegraph, or the drunken geologist that invented the telephoto lens.

It just seems that the most interesting photographers had a lot of other things going on. Today’s subject had more going on than most.

He was at least the first great photography marketer, if not the greatest self-promoter ever. He also was arguably the best portrait photographer of his day, the first to routinely use electric lights, and the first aerial photographer. In his spare time he filed dozens of patents, was the model for the main character in a Jules Verne novel, wrote over a dozen books and hundreds of articles, was the top editorial cartoonist in Europe, and sort of established the first airmail service.

That stuff is pretty great, of course, but my boy Felix was way more interesting than even those things would suggest. He hung out with people like Jules Verne, Sarah Bernhardt, and Victor Hugo. He openly despised Napoleon III when that was politically incorrect in a much more dangerous way than we use the term today. He gave the Impressionist guys (Monet, Renoir, Cezanne and others) their first exhibition largely because he knew it would upset all of the Paris art critics. He sued his brother. He made several fortunes, but was always out of money.

Unfortunately, while there is an out of print biography of him, there are only snippets of information here and there online. I’m a blogger, I know the drill: 1,000 words is all people will read these days. But 1,000 words just can’t tell the story sometimes. So I wanted to gather all that information together in one place.

I’ll warn you, though, it’s a long story. But it’s a good story. Nadar was so awesome that I already look forward to reading this post in a few years when I’ve forgotten that I wrote it. (My wife says it won’t take a few years. A month or two is sufficient for me to forget almost anything.)

The Early Years

He is very bright and very stupid. Alphonse Kerr, introducing Nadar to an editor

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon was born in France (either Paris or Lyon) in 1820. His upbringing was rather bohemian. His parents didn’t marry until he was 6. His father was a small publisher of liberal writings and Tournachon grew up on the words of Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Delacroix. As young bohemians of the time did, he took a nickname, changing his last name to Tournadar and finally just Nadar.

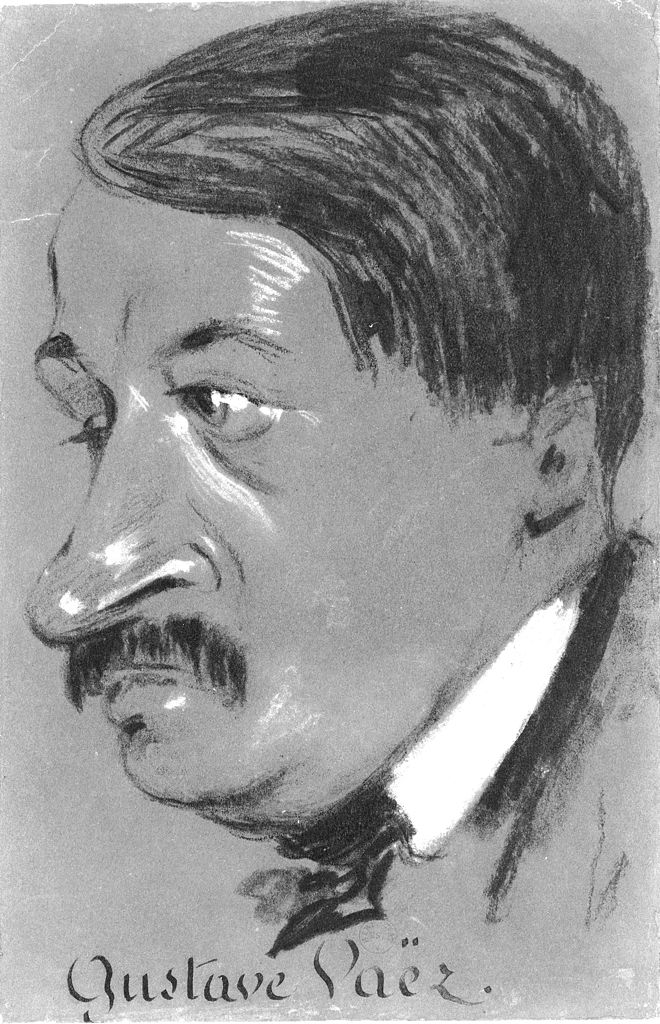

He entered medical school in Lyon after his father’s death in 1837, supporting himself by writing short articles and drawing caricatures for the local paper, using Nadar as a pseudonym. He apparently did better at this than at medical school because he dropped out after a year and returned to Paris where he lived with his mother while breaking in as a caricaturist and writer for the Paris newspapers.

- Caricature of French librettist Gustave Vaëz by Nadar. Image is in the public domain.

He was quite successful, writing columns about art, the theater, and politics, and drawing caricatures. By the age of 30 he was publishing thousands of drawings a year, numerous articles, had written his first novel, and had founded a magazine (which failed after 9 months).

1854

By 1854, Felix had made a successful career as a writer and caricaturist. His pseudonym, Nadar, was recognized throughout France. He was a tall man with blazing red hair and beard, outgoing, and with boundless energy. He socialized with the most successful artists, actors, and politician of Paris.

Despite all of his outward success, in 1854 he changed everything. He made a good income, but spent lavishly, so he was usually broke and still lived with his mother. He shocked his friends by suddenly marrying Ernistine Lefebvre, an 18 year-old from Normandy. Most of his friends assumed he had married her for her dowry, which enabled him to move out from mother’s house. But he and Ernistine remained a happy couple, staying together for nearly 60 years,

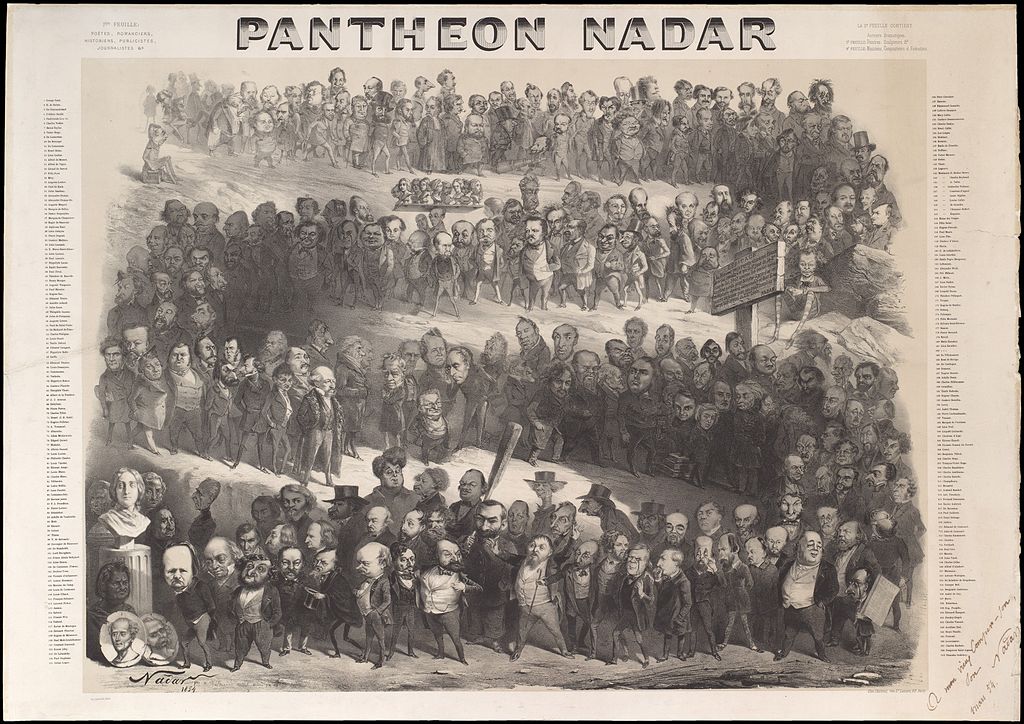

He also published the Pantheon Nadar in 1854, a huge double lithograph featuring caricatures of hundreds of prominent Parisians. He had learned the basics of photography and had photographed some of the subjects, later drawing the caricatures from the photographs. While his Pantheon was well received, he apparently lost money on this venture, too.

- Pantheon Nadar, 1854. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Work is in the public domain.

At about this time, a friend suggested Felix open a photography studio and offered to invest in it if he did. Felix was too busy to start a new venture, but he had a better idea. His younger brother Adrien was an unsuccessful portrait painter that Felix had to support. He paid for his brother to have photography lessons from Gustave Le Gray and set him up in a nice studio, at least partially funded by his friend.

According to Nadar’s later description, Adrien was a talented artist with poor work habits and little ambition. Not surprisingly, Adrien was no more successful at photography than he had been as a painter. Since his friend had loaned the money for the studio Felix felt obligated to make it successful, so he became an active participant in the studio. In his own words he “gave it everything I could: work, money, personal relations, and my pseudonym, which followed me.”

The studio became quite successful, but Adrien, who had not expected Felix to become an active partner, left and opened his own studio, calling himself Nadar Jeune (Nadar the Younger). Nadar was enraged at this and sued his brother senseless over the next three years. During the court proceedings, Felix Nadar made a short speech that still resonates today:

“The theory of photography can be taught in an hour; the technique in a day. What can’t be taught is the feeling for light; . . . it’s the understanding of this effect which requires artistic perception. What is taught even less is the immediate understanding of your subject . . . that enables you to make not just a dreary cardboard copy typical of the merest hack in a darkroom, but a likeness of the most intimate and happy kind.”

Adrien ended up disgraced and bankrupt. Of course, in a way that apparently only the French understand, Nadar, having bankrupted his brother, felt obligated to support him financially for the rest of his life.

THE Photographer of Paris

“In photography, like in all things, there are people who can see and others who cannot even look.” — Nadar

Nadar entered his new career with incredible energy and marketed himself in ways never seen before. His circle of friends were the authors, artists, and famous of Paris. He photographed them and then circulated the photographs with his studio name printed prominently. He opened his studio to them, always with refreshments handy, and they met and talked there at all hours.

Then, as now, the wealthy wanted to go to the same photographer who photographed the famous. It didn’t hurt to know that when you went for your sitting you might meet Gustave Doré or George Sand having drinks in one of the sitting rooms. Within a short time Nadar was THE portrait photographer of Paris.

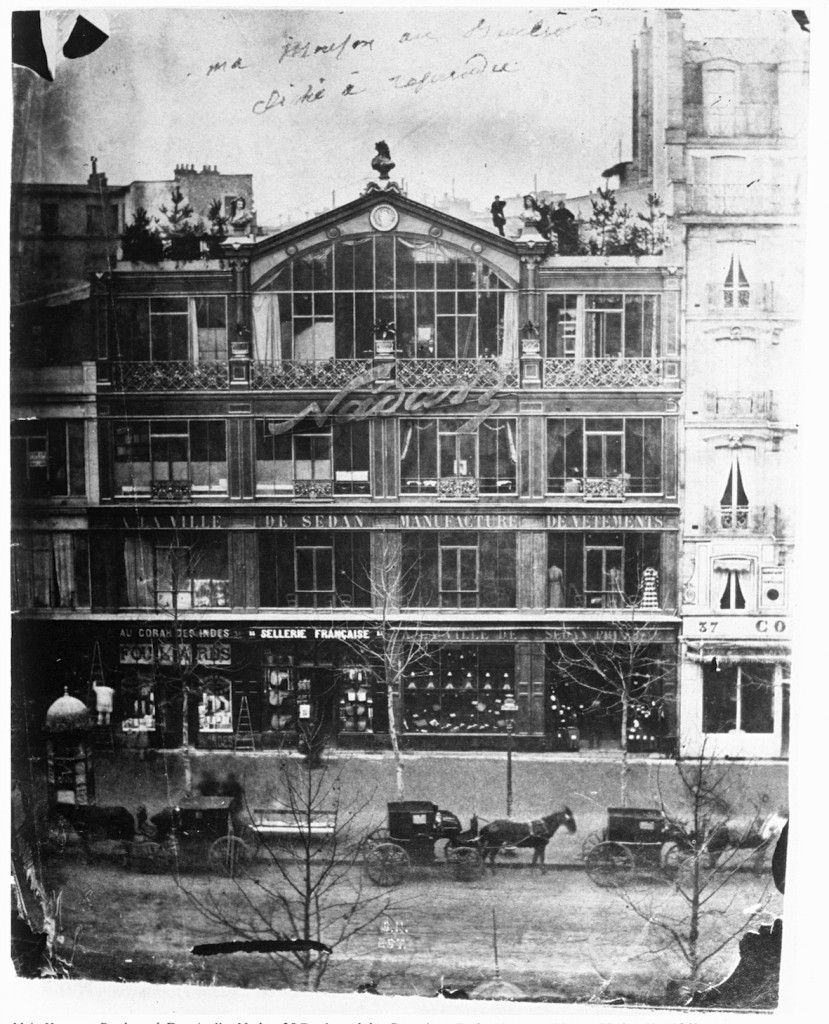

Within a few years he had outgrown his first studio and relocated to a large, four story building in the heart of Paris. He adopted red as a trademark color (possibly since he was known for his bright red hair). His studio was painted red inside and out, with his name in huge red gaslight letters across the front. He wore red velvet robes while working and meeting with clients. The interior rooms in the studio can only be described as opulent, with animal rugs, tapestries, and art objects everywhere.

- Nadar’s Studio, circa 1860.

- The building as it appears today. Image in public domain via Wikimedia Commons, credit Tangopaso

His social standing and self-promotion certainly helped his business, but Nadar was a superb photographer. His portraits were lit to give a wide dynamic range with strong side lighting on the subject’s face. He insisted on simple backgrounds that focused on the subject and patented a process to fade out the edges of the photograph to a low contrast. He wanted nothing to distract from the subject’s face. He usually insisted they wear dark clothing for the sitting and often hid the subjects hands, placing all emphasis on the face. The result was a strong 3-dimensional effect with a lifelike pose at a time when portraits were generally stiff and uniform.

- Sarah Bernhardt, photograph by Nadar, about 1864. J Paul Getty Museum Open Content Program.

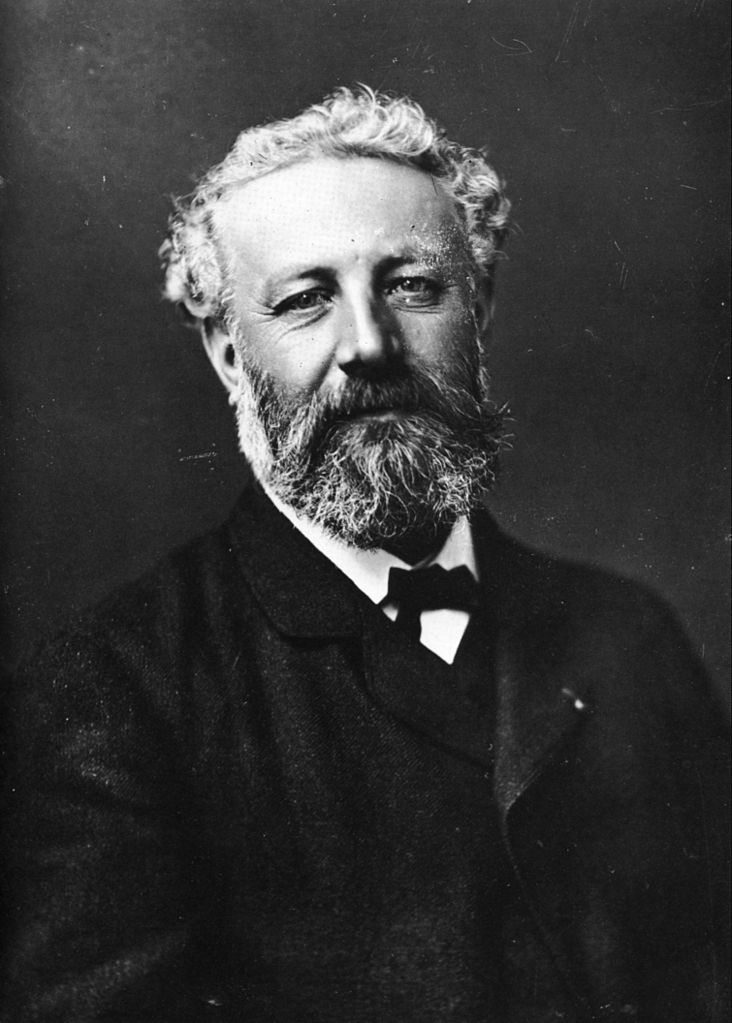

- Jules Verne, photograph by Nadar, circa 1878. Restoration by JDCollins, via Wikipedia commons.

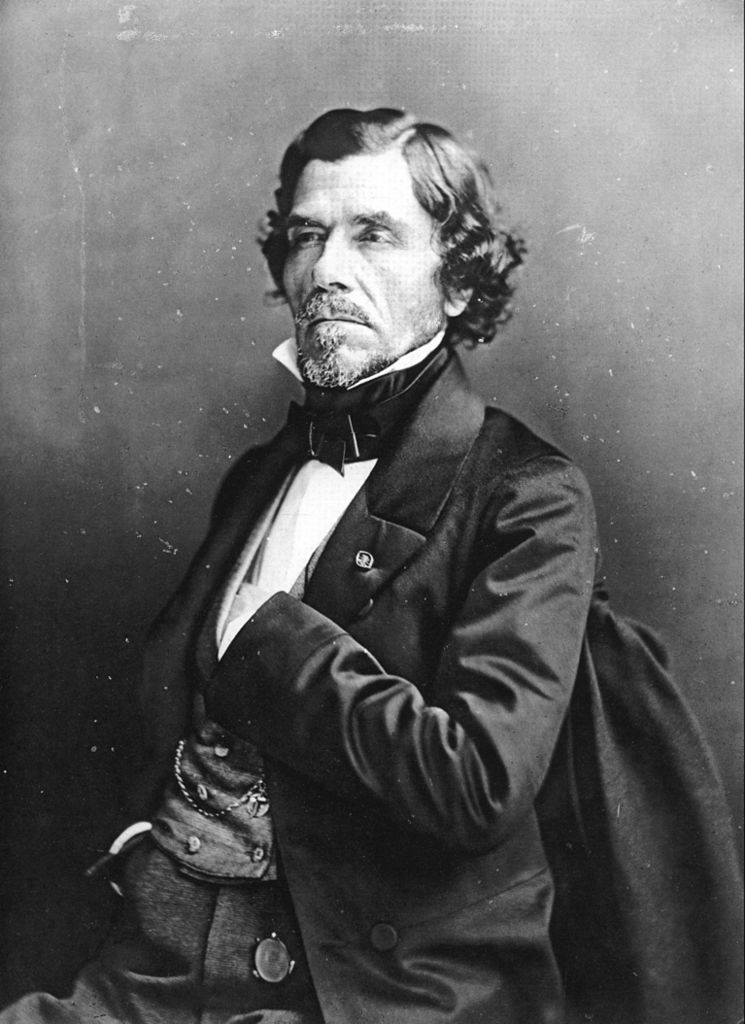

- Eugene Delacroix, portrait by Nadar, date unknown. Image is in the public domain.

(A superb slide show of many of Nadar’s best portraits has been done as part of the Masters of Photography series and is available on YouTube.)

Nadar felt his success was largely because of his ability to understand his subjects psychologically. His attitude of cheerful cynicism was quite amusing. He preferred not to photograph women, because “the images are too true to nature to please the sitters, even the most beautiful”. He also said when a couple returned to examine their proofs, the wife always looked first at the image of her husband . . . and so did the husband. Actors were the vainest sitters, he felt, followed closely by soldiers.

He made just as much fun of his friends. Writers Honore de Balzac, Theophile Gautier, and Gerard de Nerval subscribed to a theory that a person’s image is made up of many layers. They feared having their photograph taken because they believed each photograph stripped away one of those layers. Nadar said that given their size (all were rather fat men), the loss of a layer or two should be of no consequence.

- Theophile Gautier, photographed by Nadar. Image is in the public domain.

Nadar wasn’t just gifted artistically, he was technically ahead of his time. While the first electrically lit studio is generally credited to Van der Weyde in 1877, Nadar was using battery powered electric lamps in studio by 1858.

As Nadar described it (poorly translated from French by me with the aid of Google translator – any errors are mine):

“At that time we did not have precious portable batteries or generators. We were reduced to the bulky inconvenience of Bunsen batteries. I had installed by an experienced electrician fifty elements that I hoped would provide the required light. I began to experiment on my simple person and my laboratory staff. These first pictures were poor and even detestable — opaque blacks, no details in the face, the eyes extinguished by excess light or suddenly stung like two nails.

I added a second, softened light into the shaded parts. I dimmed the light by placing a frosted glass between the lens and the model, I arranged reflectors of white duck, and finally a double set of large mirrors reflecting onto the shaded parts. Finally I could get shots at equal speed to daylight in my studio with the quality I desired.”

Even in his experimentation, Nadar didn’t simply use the lights to allow shorter exposure times, as most who came after him did. It’s obvious from the description and portraits above that he used lights for effect, creating mood and detail that were unusual for portraits of the day.

His experimentation with electric lighting was a brilliant innovation. Perhaps even more brilliant was how he used this innovation for marketing.

“Each nightfall, we set our lights in the window. The crowd on the boulevard was attracted like moths to light, many curious friends or indifferent, could not resist climbing the stairs to see what happened there. These visitors, from all classes, unknown or even famous, were more than welcome, providing us free stock models quite ready for the new experience. This is how I photographed among others those evenings Niepce de Saint-Victor, G. La Landelle, Gustave Doré, Alberic Second, Henri Delaage, Branicki, É. Pereire, Mires, Halphen, and finally my neighbor across the street and friend, Professor Trousseau.”

Nadar had made a good life for himself, living in a 4 story studio / home in central Paris that looked like a hot nightclub from the outside and was decorated like a Sultan’s palace inside. He was so famous that Victor Hugo (then in self-imposed exile) once sent a letter simply addressed “Nadar” and it arrived at the studio promptly.

His friends were the luminaries of France when France was the intellectual and cultural center of the word. Those renowned writers and artists considered Nadar not only one of them, but at the time perhaps the most famous of them. Jules Verne, for example, said Nadar inspired his novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, and he based the main character of From Earth to the Moon on Nadar.

But just being the top portrait photographer in France, the first to use electric lights artistically, a famous caricaturist, and widely published author wasn’t enough for Nadar.

The Heights and Depths

Photography is a science that has attracted the greatest intellects, and an art that excites the most astute minds—and one that can be practiced by any imbecile. Nadar

Into the Air

Nadar and several of his friends, notably Jules Verne and Victor Hugo, were fascinated by flight. In his day, that meant gas or hot-air balloons, although they were all convinced that heavier than air flight was in the near future. Nadar began ballooning sometime after 1850 and as early as 1855 was attempting to take aerial photographs from balloons.

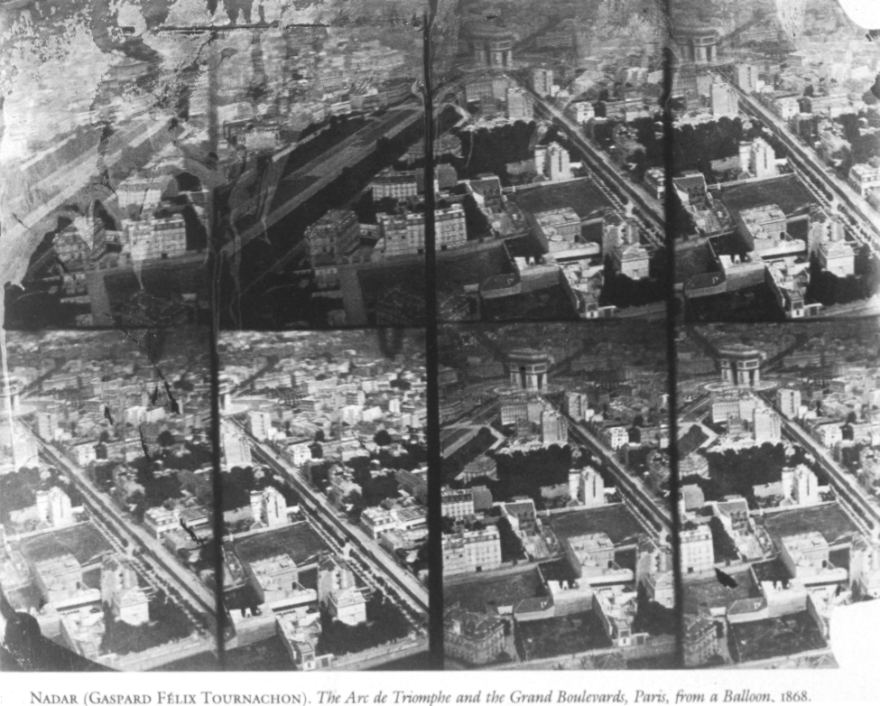

He had numerous difficulties at first, but eventually discovered that hydrogen sulfide was escaping from the balloon, ruining his plates during development. In 1858 he finally succeeded in making the first aerial photograph, taken of the village of Petit-Becetre from a balloon tethered 80 meters above the ground.

These early photographs have been lost, with his earliest surviving aerial photograph being one of Paris taken in 1866.

- Nadar: Images of Paris from Balloon. 1868? Images are in public domain.

There is some argument about the date of this first successful aerial photograph. Nadar later claimed he had been successful in 1855, but this was probably an effort to insure primacy for patents. Nadar was convinced aerial photography would replace surveying, mapmaking, and replace much of military espionage. (All of which did occur, but not as quickly as Nadar had hoped.) He filed patents for a remote shutter control, a special tent, developers, and other apparatus for taking photographs from a balloon.

Nadar was always a master of publicity, but in the case of ballooning it was not just self-publicity. He was a true believer in the future of flight. Quite ahead of his time, he felt that balloons would be powered by some form of screw or propellor, and that heavier than air machines would soon replace balloons. Along with Jules Verne he founded the Society for Promotion of Heavier than Air Locomotion, and published L’Aeronaute, a journal dedicated to discussing the future of flight, illustrated by his friend Gustave Dore.

He also began construction on what was, at the time, the largest balloon ever made, which he called Le Geant (the Giant). While his motives were largely scientific, Nadar was never one to miss an opportunity for a little self-promotion. He printed announcements that he was constructing The Giant and financing the entire cost (over 200,000 francs) himself. He had publicity pictures made of himself in a balloon basket which were widely distributed.

- Image is in the public domain.

An impressive shot, but this other version of his wife Ernestine and him shows it was a simple studio prop in front of a painted backdrop.

- Image is in the public domain.

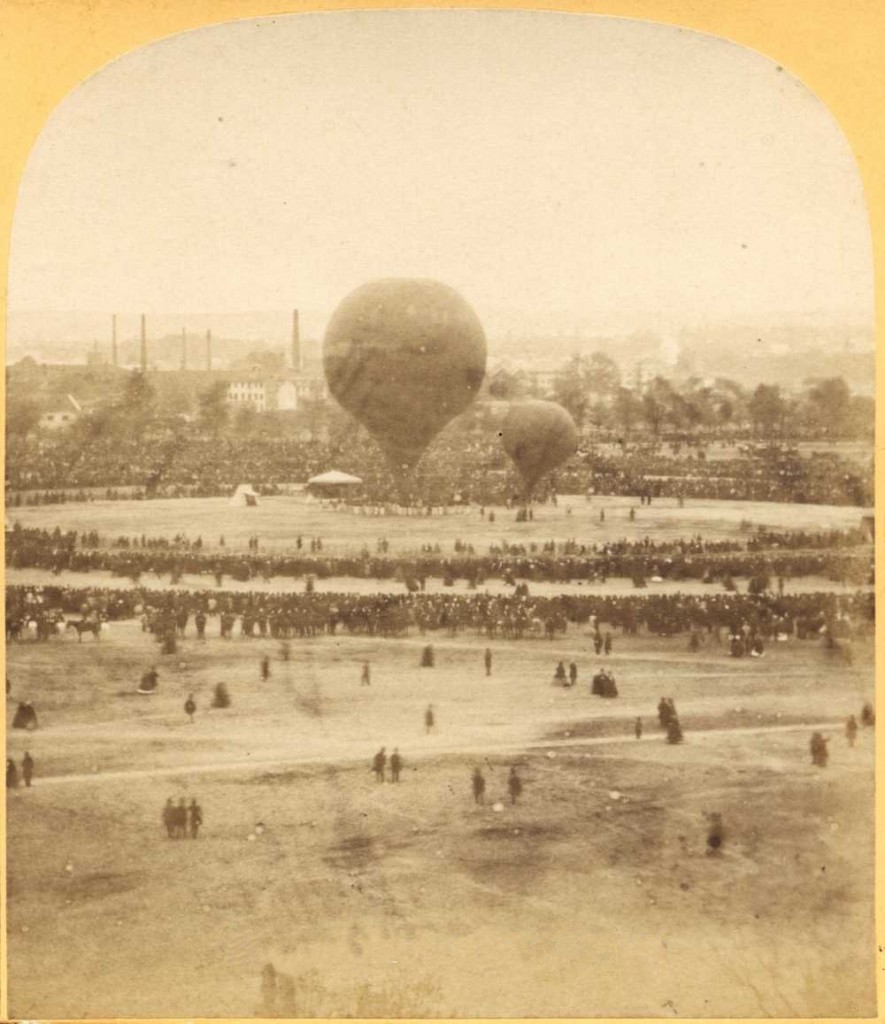

Le Geant was truly gigantic, standing 12 stories high, containing 212,000 cubic feet of gas enclosed by 22,000 yards of silk sewn into a balloon by 200 seamstresses. The basket of the balloon was designed to resemble a two-story cottage (although some detractors said it looked more like a garden shed), and had small cabins, a lavatory, galley, darkroom, and room for up to 20 passengers. It first flew on October 4, 1863, carrying 13 passengers who paid 1,000 francs each. The launch was viewed by a crowd of nearly 20,000 spectators who were supposed to have paid a franc each for admission, although most simply stood outside the ‘paying customer’ area.

- Le Geant preparing to take off, 1863. Photo is credited to Nadar. Image is in public domain.

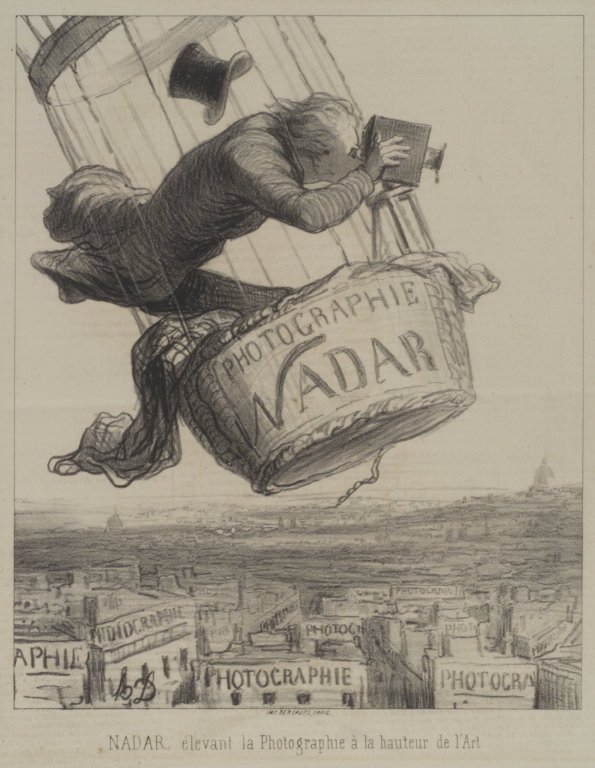

The amount of publicity the event generated was incredible. Nadar, the caricaturist, found himself the subject of a caricature by Honoré Daumier mocking the amount of advertising he obtained from the event. (Nadar later said he and Daumier had planned the caricature together. Certainly Nadar welcomed any and all publicity, so the story is plausible.)

- Daumier: Nadar Elevant la Photographie. Brooklyn Museum.

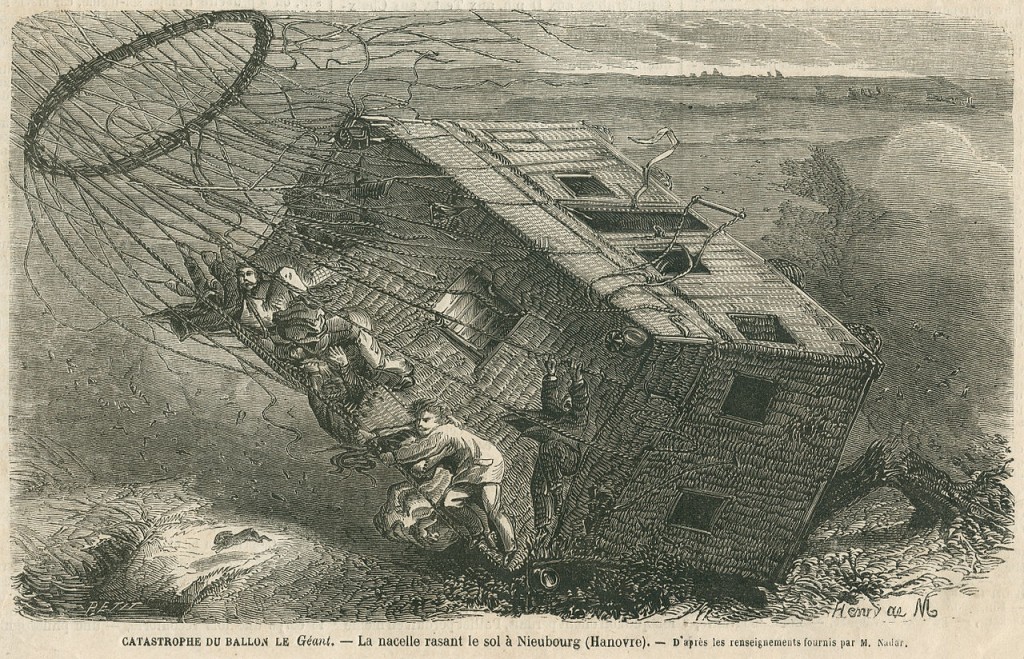

The second flight of The Giant was made October 18; the plan this time was for a long distance flight to Poland or Germany. The launch was witnessed by an even larger crowd, including Napoleon III and the King of Greece. Unfortunately, the balloon was carried along by a gale for 17 hours and attempted landing in 30 mile-per-hour winds. The landing anchors gave way and the balloon dragged and bounced for miles before finally deflating. Nadar broke his legs and all the passengers, including his wife, were injured.

Nadar was never one to let a devastating setback bother him. He immediately commissioned dramatic illustrations of the event, which he copyrighted and sold to papers and journals all over Europe.

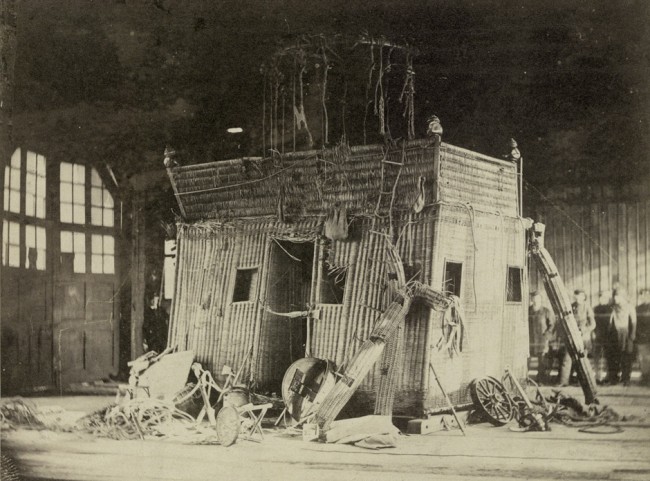

He wrote and published Memoires du Geant.He used the funds from the publications to have the balloon and gondola repaired and exhibited all over Europe. Le Geant made several further flights, but these were simply local up-and-down affairs with no further long-distance flights.

- The gondola of Le Geant after the crash.

Nadar probably never came close to recovering his investment in The Giant, but the amount of publicity he received was incalculable. Nadar did not lose his love of ballooning, and continued to fly for many years.

And in a stroke of genius, he turned the entire disaster with Le Geant around, using it as an example that only heavier-than-air flight could ever be safe. He published Le Droit au Vol (The Right to Flight) in which he campaigned for heavier-than-air ships powered by steam engines with rudders and elevators so that they could be steered. Such ships had been proposed before, but it was Nadar who coined the term ‘dirigible’ (meaning ‘to steer’) to describe them.

It’s hard for us today to realize just how much larger than life Nadar was during this time. His friend Victor Hugo, never one to employ understatement, wrote a long “Letter on Flight” in support of Nadar’s views. In the letter, which was widely published, he compared the flight of The Giant to Christopher Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic, and compared Nadar’s courage and perseverance to that of Voltaire and Martin Luther.

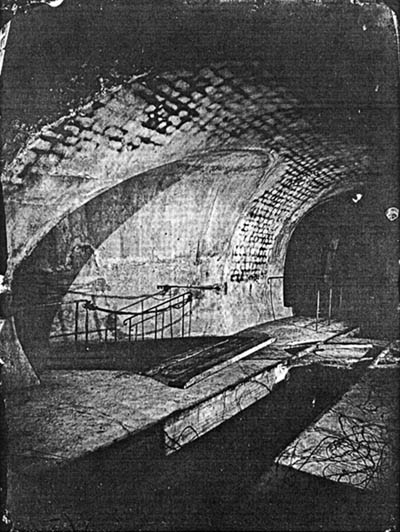

Down to the Catacombs

Paris has long been known as City of Light (Light as in Enlightened, not as in 100 watts), but in the 1850s and 60s, it was proudest of being the City of Sewers. At a time when most of the world considered proper sewage disposal making sure no one was walking below the window when you emptied your chamber pot, Paris had over 560 kilometers of large underground sewers and storm drains. During Nadar’s time, these were something of a tourist attraction and people actually took boat rides by torchlight through the underground sewers.

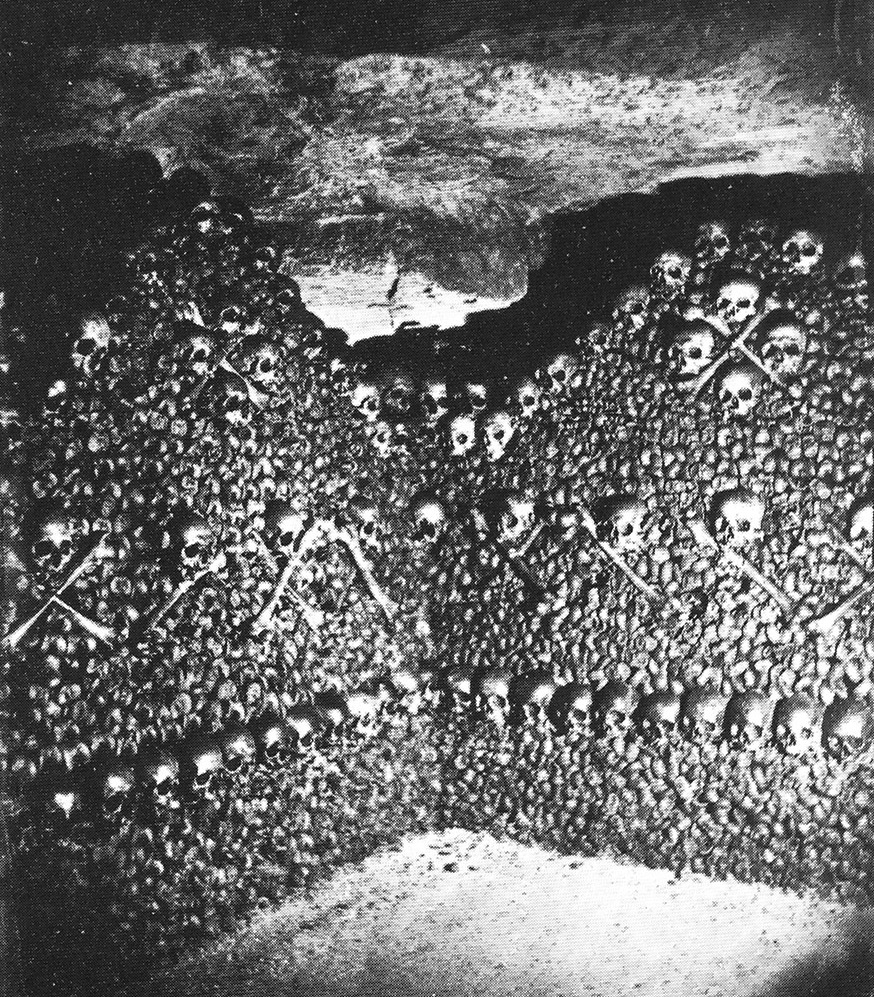

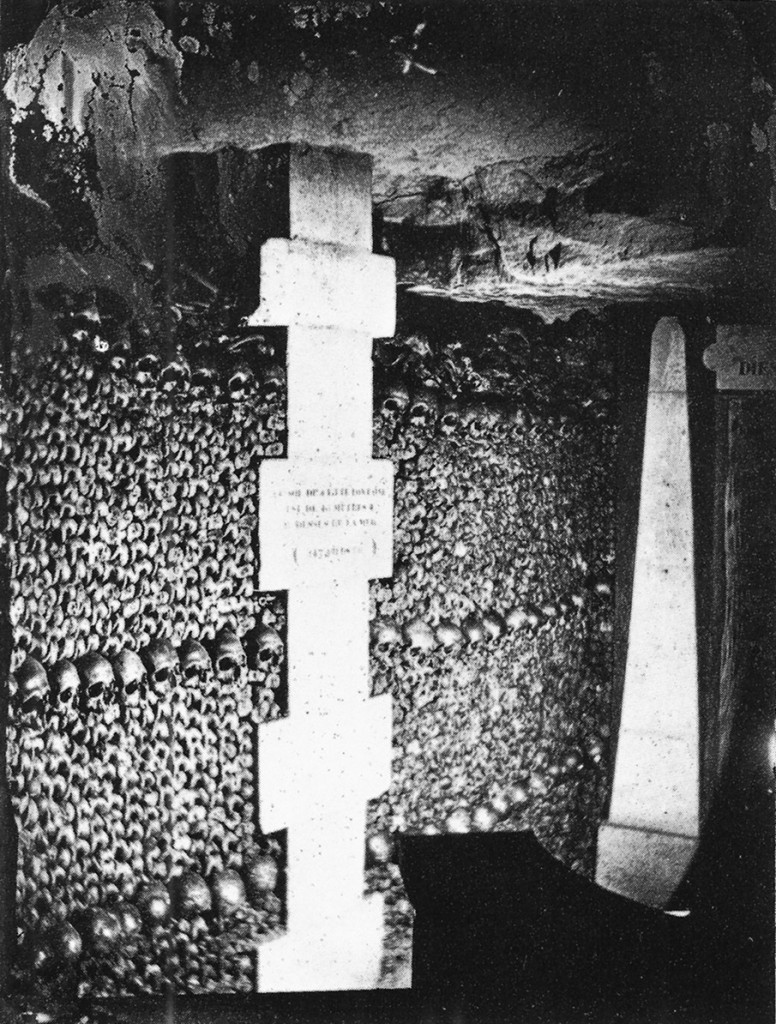

Paris also has unique underground catacombs or ossuaries containing the bones of over 6,000,000 people. Initially, the bones were removed from overcrowded cemeteries and piled in the empty caverns remaining from old mines. Around 1815, the director of mine inspections, Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, had the ossuaries transformed, neatly stacking the bones in patterns, adding funeral monuments, inscriptions, and displays (some of rather questionable taste). The catacombs became such a tourist attraction that special permission was required to visit them, and they were only open on certain days.

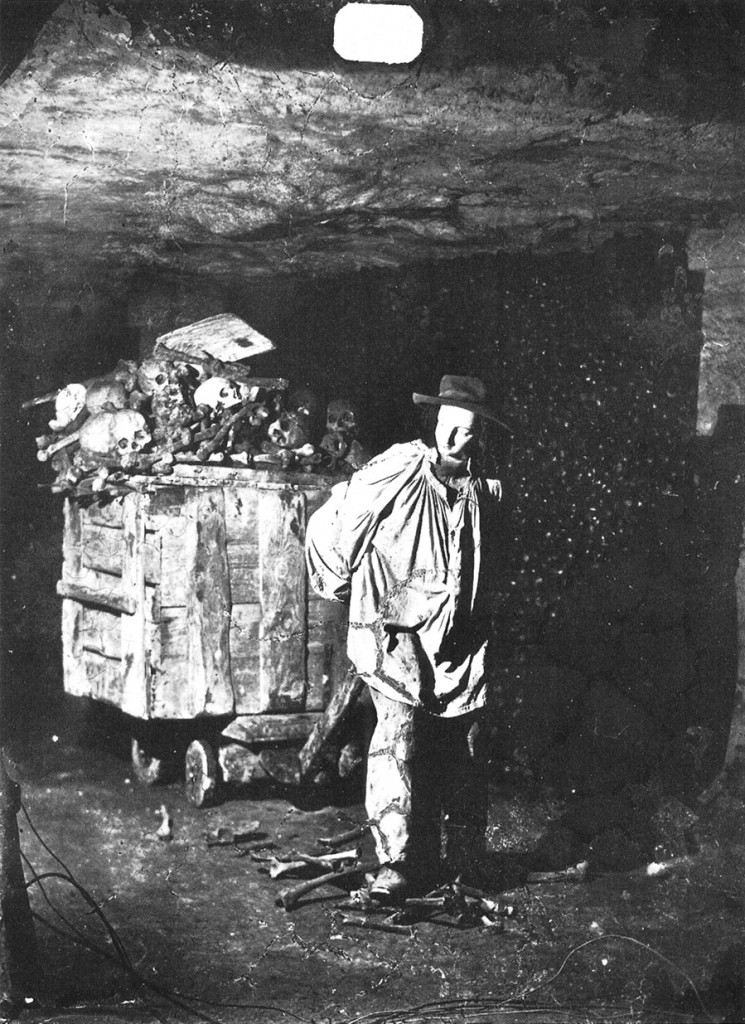

Nadar obtained permission to photograph both the sewers and catacombs. He did it for several reasons: there was demand for images of these places many people knew of, but few could visit; he wanted to experiment with the battery powered lights he used in his studio; and, of course, there would be significant publicity in obtaining photographs that no one else had been able to obtain.

Even with his electric lights, the duration of exposure was too long for him to use human models, so he dressed and posed mannequins as workman, visitors, and others. (All images below are by Nadar and are in the public domain.)

His pictures of the catacombs were made in 1861 and exhibited in 1862 and 1863. While the images and exhibitions were a success, Nadar lost money on the venture. Transporting his lights and equipment into the catacombs was expensive and time consuming. As always, Nadar patented his techniques for ‘photography by electric lights’ but it seems doubtful he ever made a dime from them.

What’s more, he found the actual catacombs really didn’t meet his expectations. In addition to the mannequins, he had to use careful framing, and in some cases a lot of reconstruction to make the images more dramatic. As he described the catacombs later, “They are a place everyone wants to see, but no one wants to see again.”

His photographs of the sewer system were probably made in 1864. He found the sewers even more disappointing than the catacombs, though. He had expected something like the description of the sewer system made by Victor Hugo in Les Miserables, but he found the efficient and modernized underground canals of the new Paris sewers simply industrial and efficient. The cost of making the 23 images he obtained was extreme and he stopped the project well before he was happy with the results.

Air Mail and Microfilm

Nadar patented his aerial photography methods, but the technique proved too difficult and expensive to replace surveying. Napoleon III offered him 50,000 francs to set up a military aerial photography corps for his upcoming war with the Prussians, but Nadar hated Napoleon III so he declined.

Napoleon III certainly wasn’t Napoleon I. By the time he got around to declaring war on the Prussians, they had been preparing for months. The Prussians immediately battered the French army, captured Napoleon III, forced him to abdicate and exiled him to England. The French formed a new Republican government, but when the Prussian army entered France the new government and most of the army beat a ‘strategic retreat’ into the countryside. The Prussians surrounded Paris and started a siege that lasted months. Paris was completely cut off and had no communication with the outside world.

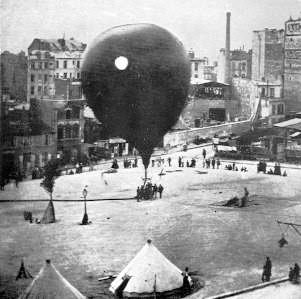

Nadar had remained in Paris and organized his ballooning friends and a few old, moth-eaten balloons into the 1st Balloon Company. Initially he only made observation flights, marking down the various Prussian positions around Paris (not that the French could do much about it). He also dropped propaganda leaflets over the Prussian troops. (The French, knowing Nadar’s ways, assumed he was dropping advertising literature.) Since the Prussians couldn’t seem to do much about his balloon observations, he pushed the French authorities to allow a balloon to carry dispatches and mail out of Paris.

There was the traditional bickering within the government, notably with the Paris Postmaster claiming he should be placed in charge of balloon mail delivery, despite the fact he had no balloons. Finally, on September 23rd, Nadar sent the leaky old balloon ‘Neptune’ piloted by Jules Durouf and loaded with 125 kilos of dispatches and mail aloft. This time, as the balloon floated over the Prussian lines, Durouf threw out handfuls of business cards for Nadar Photographe’, each inscribed by Nadar “Compliments to Kaiser Wilhelm and Monsieur von Bismarck – Nadar“. So perhaps the French assumptions about Nadar’s propoganda wasn’t too far off the mark, after all.

- Photography of the Neptune preparing for flight. Hulton Deutsch / CORBIS

The balloon made it over the Prussian lines and within days the London Times had published a personal letter from Nadar to the British people that he had included in the balloon’s dispatches.

Paris set up a balloon works to make more balloons. A total of 79 balloon flights left Paris over the next few months, providing not only communications but an incalculable morale boost. Getting messages back into Paris, though, proved a bit more difficult. A balloon leaving Paris simply had to cross the Prussian blockade and land anywhere else in France. Getting a balloon to drift back into Paris was much more difficult.

The solution was to take carrier pigeons out on the balloon flights and then return messages to Paris via the pigeons. There is an obvious limitation, of course. A balloon could carry hundreds of kilograms of mail, but a carrier pigeon at most a few ounces. Once again, it was Nadar who found a solution.

Another Paris photographer, Rene Dagron, had developed the technique of photographing multiple letters mounted on a flat board. A single roll of collodion negative film could contain over 1,000 letters and was small enough to be carried by a carrier pigeon. Nadar sent Dagron and his equipment out of Paris on a mail balloon and by November microfilmed mail was getting back to Paris by carrier pigeon.

The Later Years

After France and Prussia negotiated an end to their war, life began returning to normal in France. Nadar’s studio continued to be busy and his reputation was, if anything, enhanced after the war. He had become friends with a group of painters whose works were considered substandard and even bizarre, and therefore were denied exhibition at the famous Paris Salon. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc. and Nadar hosted an exhibition of their works at his studio.

As Nadar knew it would be, the exhibit was scorned by the French art critics. Louis Leroy, in particular, wrote scathing reviews calling the paintings ‘unfinished impressions’. Of course, eventually Monet, Degas, Renoir, Cezanne, and the other artists of the Anonymous Society became known as the Impressionists. The combination of horrible reviews and Nadar’s involvement made the exhibit irresistible, and people packed the studio to see it. Oddly, while the French were not impressed by the works, foreign collectors bought most of the paintings on exhibit. (Which is one reason so many French Impressionist paintings are exhibited in non-French museums.)

Nadar’s son Paul began taking over the photography studio, and Nadar returned to writing in his later years. He wasn’t quite done originating, though. In 1886 he and Paul published the first Photographic Essay, celebrating scientist Michel Chevreul’s 100th birthday. Pictures of Chevreul (taken by Paul) were accompanied by the text of the interview written by Nadar.

Nadar’s final book, When I Was a Photographer, was a memoir written in 1900 when Nadar was 80. The facts are, shall we say, not always as accurate as they could be, but it remains a fascinating read.

Nadar spent the last decade of his life caring for Ernestine, who had become an invalid following a stroke. He lived about a year after her death ‘simply to gather his affairs in order’ before passing away peacefully just short of his 90th birthday on March 23, 1910. Despite all of his showmanship and self-promotion, the man who had been the best portrait photographer in Europe, the first to work with electric lights, who developed aerial photography, and microfilm, had a rather modest self-assessment.

A bygone maker of caricatures, a draftsman without knowing it, an impertinent fisher of bylines in the little newspapers, mediocre author of disdained novels… and finally a refugee in the Botany Bay of photography. (Nadar, Self-description, 1899)

He was far more than that.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

March, 2014

Sources

Barnes, Julian: Levels of Life. Alfred A. Knopf, London, 2013.

Bocard, Helene: Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon). Oxford University Press, 2009. via MOMA.org

Gosling, Nigel: Nadar. New York Metropolitan Museum by Alfred A. Knopf, 1976.

Hambourg, et al.: A Portrait of Nadar. Met Publications on Demand, 1995.

Holmes, Richard: Falling Upwards: A History of Balloon Flight. Random House, New York, 2013.

Larson, Sharon: Rethinking Historical Authenticity: Photography, Nadar and Haussmann’s Paris. Equinoxes: A Graduate Journal of French and Francophone Studies. Brown University Press, 2005.

Meltzer, Steve: The Incomparable Nadar. Imaging Resource, March, 2013.

Nadar, Felix: My Life as a Photographer. Translated by Thomas Repensek. MIT Press via JSTOR archives. NOTE: While this is superbly entertaining, it was written during the last years of Nadar’s life and is widely believed to be, let us say, a wandering story of things that probably happened.

Whitmire, Vi: Nadar (Gaspard Felix Tournchon) (1820-1910). International Photography Hall of Fame & Museum, 2004.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

pl capeli

-

Wolfram Schenck

-

Sean Tomlinson

-

Michael Clark

-

gianpaolo

-

JoostL

-

James

-

Pablo Garcia

-

Max Berlin

-

Ben

-

Sggs

-

intrnst

-

Samuel H

-

John Krumm

-

jean-louis salvignol

-

Phil Lurkin

-

Jim Maynard

-

jean-louis salvignol

-

richard

-

Arn

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

David

-

Admiring Reader

-

CarVac

-

Peter Bruggemans